Spam Rising? Emonet World’s baddest botnet is back with stolen passwords and email

If you’ve noticed an uptick of spam that addresses you by name or quotes real emails you’ve sent or received in the past, you can probably blame Emotet. It’s one of the world’s most costly and destructive botnets—and it just returned from a four-month hiatus.

Emotet started out as a means for spreading a bank-fraud trojan, but over the years it morphed into a platform-for-hire that also spreads the increasingly powerful TrickBot trojan and Ryuk ransomware, both of which burrow deep into infected networks to maximize the damage they do. A post published on Tuesday by researchers from Cisco’s Talos security team helps explain how Emotet continues to threaten so many of its targets.

Easy to fall for

Spam sent by Emotet often appears to come from a person the target has corresponded with in the past and quotes the bodies of previous email threads the two have participated in. Emotet gets this information by raiding the contact lists and email inboxes of infected computers. The botnet then sends a follow-up email to one or more of the same participants and quotes the body of the previous email. It then adds a malicious attachment. The result: malicious messages that are hard for both humans and spam filters to detect.

“It’s easy to see how someone expecting an email as part of an ongoing conversation could fall for something like this, and it is part of the reason that Emotet has been so effective at spreading itself via email,” Talos researchers wrote in the post. “By taking over existing email conversations and including real Subject headers and email contents, the messages become that much more randomized and more difficult for anti-spam systems to filter.”

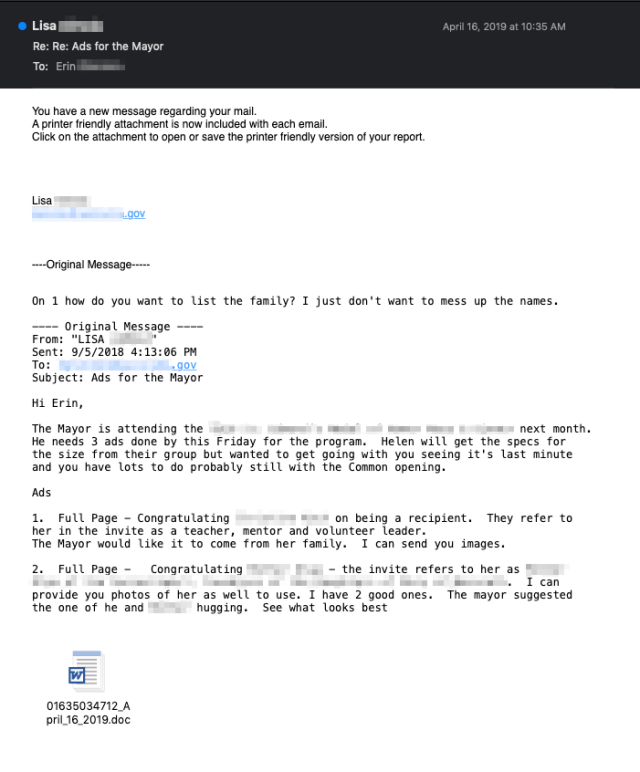

Using the Emotet spam message shown above, which incorporates a previous conversation between two aides to the mayor of a US city, here’s how the ruse works, according to Talos:

- Initially, Lisa sent an email to Erin about placing advertisements to promote an upcoming ceremony where the mayor would be in attendance.

- Erin replied to Lisa inquiring about some of the specifics of the request.

- Lisa became infected with Emotet. Emotet then stole the contents of Lisa’s email inbox, including this message from Erin.

- Emotet composed an attack message in reply to Erin, posing as Lisa. An infected Word document is attached at the bottom.

The use of previously sent emails isn’t new, since Emotet did the same thing before it went silent in early June. But with its return this week, the botnet is relying on the trick much more. About 25% of spam messages Emotet sent this week include previously sent emails, compared with about 8% of spam messages sent in April.

203k stolen email passwords

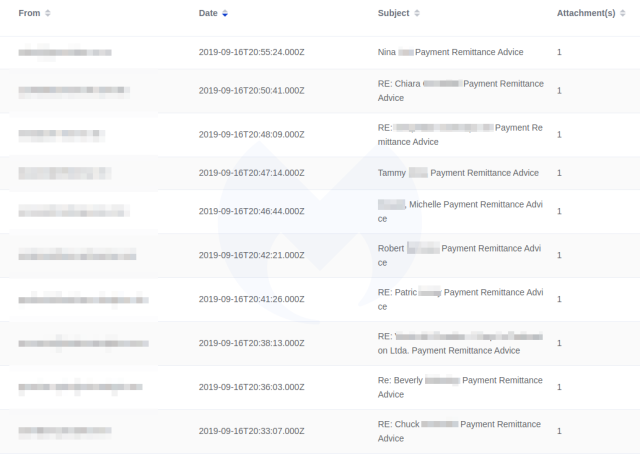

To make sending the spam easier, Emotet also steals the usernames and passwords for outgoing email servers. Those passwords are then turned over to infected machines that Emotet control servers have designated as spam emitters. The Talos researchers found almost 203,000 unique pairs that were collected over a 10-month period.

“In all, the average lifespan of a single set of stolen outbound email credentials was 6.91 days,” the Talos post reported. “However, when we looked more closely at the distribution, 75% of the credentials stolen and used by Emotet lasted under one day. Ninety-two percent of the credentials stolen by Emotet disappeared within one week. The remaining 8% of Emotet’s outbound email infrastructure had a much longer lifespan.”

A separate post from Malwarebytes said Emotet has brought back another tactic it first introduced in April—referring to targets by name in subject lines.

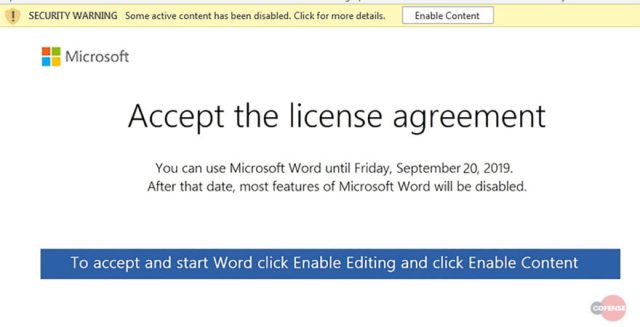

Once opened, the documents attached to the emails claim that, effective September 20, 2019, users can only read the contents after they have agreed to a licensing agreement for Microsoft Word. And to do that, according to a post from security firm Cofense, users must click on an Enable Content button that turns on macros in Word.

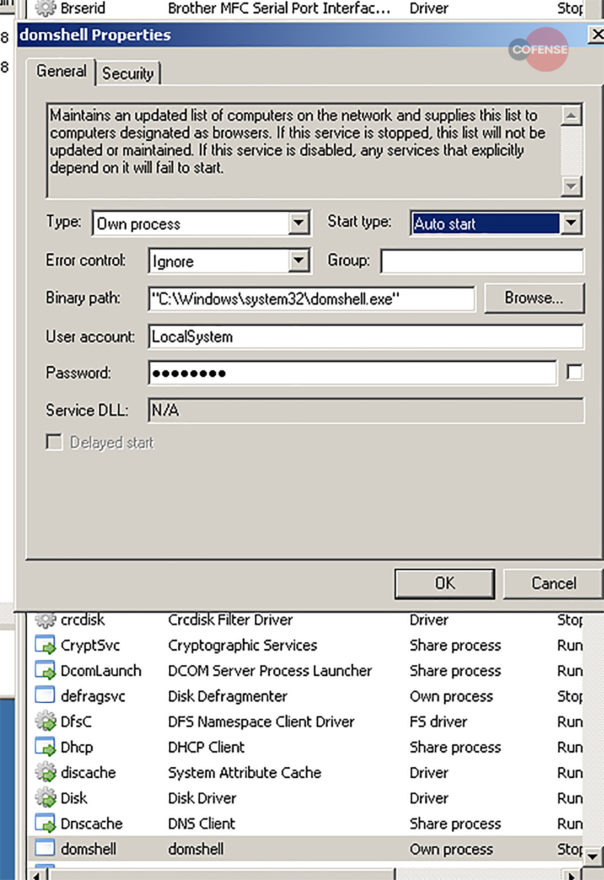

“After Office macros are enabled, Emotet executables are downloaded from one of five different payload locations,” Cofense researchers Alan Rainer and Max Gannon wrote. “When run, these executables launch a service, shown [below], that looks for other computers on the network. Emotet then downloads an updated binary and proceeds to fetch TrickBot if a (currently undetermined) criteria of geographical location and organization are met.”

One of the ways Emotet spreads to other devices on the same network is by exploiting easily guessed passwords.

With its massive pool of stolen emails and email server passwords, professional-grade malware, and sleek social-engineering tricks, Emotet has rightfully come to be regarded as one of the world’s most threatening botnets, at least for people using Windows. People should counter the threat by considering the use of Windows Defender, Malwarebytes, or another reputable antivirus program. Another measure: being highly suspicious of every attachment or link received by email, even when it appears to come from someone you know. People should also use strong passwords for every connected device in their network to prevent Emotet infections from spreading inside a local network.

Malwarebytes has indicators of compromise here that readers can use to determine if they have been targeted by Emotet.

From ArsTechnica